Click here to read a piece entitled "Seek Your Balance" which I recently contributed to the Solid Roots Yoga "Live a Grounded Life" blog.

Many of us long-time students with established practices—favorite styles of practice, favorite (and least favorite) poses, favorite teachers, and favorite classes on the studio schedule—have developed on-the-mat habits and routines. That’s what happens when you practice yoga for a while: you learn what you like and dislike, and then seeking that out becomes habitual. That kind of repetition and routinization is part of how we come to have a steady, dedicated, and lasting relationship with yoga. Remember, Patanjali’s fourteenth Sutra says that one’s practice is most excellent when it is tended to consistently, continuously, and enthusiastically. Habit, in that sense, is very much a good thing. And without it, we run the risk of never fully committing or of failing to set an adequate foundation.

On the other hand, yoga was born from a deep, driving desire to be and act and think differently—to challenge the very norms and protocols which were being dictated to the ancient yogis. Those early practitioners were certain that the “rules” which they were told necessarily governed human behavior and consciousness could be bent, altered, broken, and even discarded. And to positive effect. Much of yogic literature and philosophy is the data recordings, journal entries, and memoirs of those who challenged their own habits and routines, and then wrote about what they experienced and observed. Yoga’s essence is steeped in change and transformation.

Again, we need those favorite and familiar parts of our practice. We need a relationship with a teacher we like and trust. We need a reliable schedule of classes which coordinates with our off-the-mat schedule. It is good to know that you are refreshed by restorative poses and irritated by flow sequences. It is good to know that your body responds best when you do low-to-the-ground hip-openers before Sun Salutations. It is good to know that you are a strong and flexible yogi who is capable of many beautiful postures, but you are still lousy at balancing on one leg no matter how much you prepare for it. That only comes from showing up to practice over and over and over again. Knowing those kinds of things about yourself and your practice means that you are in fact practicing which is fantastic.

Now that yoga is your habit—now that you are there dependably, you know the basics, you make good choices—it’s time to shake it up. Do something different. Challenge your habits.

I have had a few conversations with students about this recently. I led a class which focused on a fairly lengthy series of deep squatting shapes (Malasana and related variations) followed by a few long forward folds like Uttanasana and Paschimottanasana. Afterward a student approached me to say that she had never experienced those poses in that order before, and that she loved how limber and open her hips and legs felt during the forward folds. The squatting shapes weren’t unfamiliar to her, but using them as preparation for forward folding was new. She tried something different, and it worked quite well for her.

I also recently presented a class which focused specifically on Chaturanga Dandasana, but not as part of a vinyasa flow the way it is often practiced these days. Instead, we treated it in a form-based way for its own sake. Part of the point was to experience being in Chaturanga Dandasana for a period of time without using it as a transition into something else. One student in particular really struggled with this. Their Chaturangas are beautiful, and the challenge for them was not in getting into the pose. The challenge was staying in the pose, and not turning it into Upward-dog. As soon as they bent their elbows and lowered their trunk, they would immediately straighten their arms and lift their chest for the back bend which their body has been trained to assume comes next. After years of vinyasa flow, the habit of Down-dog—Chaturanga—Up-dog—Down-dog—Chaturanga—Up-dog—Down-dog—Chaturanga—Up-dog is thoroughly embedded in their muscle memory. It’s like a reflex now: such a strong routine that no matter how many times I told them not to, and no matter how many times they told themselves not to, they would lift immediately into Upward-dog without pausing to savor the beauty of Chaturanga all by itself. It was equal parts informative, frustrating, and amusing for both of us. And a perfect example of how habits act both positively and negatively within our practice—the fact that this person has been disciplined enough over some time to develop such strong skills of alignment and movement is commendable, but, on the other hand, it’s the sign of a kind of loss of control. In that particular circumstance, they are not acting mindfully and consciously. Instead, they have given over to rote grooves. To return to a state of abhyasa (practice in a strong sense, Practice with a capital P), they will have to challenge those habits.

We have been playing purposefully with this notion in the DK class recently by rearranging the typical sequence of poses into something less expected, and observing the effects it has on the body and mind. If you are used to a particular order of events—if your go-to sequence is either formally or partially choreographed—it can be shocking and disorienting to do otherwise. But I do recommend it once in the while.

If you are well-versed in the Ashtanga Primary Series, for instance, try practicing it in the reverse order: from the end of the sequence to the beginning. That’s an example of a type of very formal choreography. Maybe your practice habits aren’t that strict, but are predictable in their own way. If you always start with standing poses, try saving them until the end instead. Treat Sun Salutations as the peak rather than the warm-up. Or try getting through a whole practice without Down-dog, which can be deceptively challenging if it typically makes a frequent appearance in your practice.

Another way to challenge your practice habits is to attend a class that features a style you don’t know or think you don’t like. If you’re a vinyasa junkie, try a Yin or Restorative class. If the mere thought of perpetual motion exhausts you, grab a water bottle and a towel and get to a flow class. Go to a studio across town and try a new teacher. Or find a studio to visit when you’re traveling that offers a style you can’t get locally. There are endless variations on this theme.

The point is that, in some ways, “yoga” and “habit” fit perfectly well together. Our yoga should be a habit in the sense that we choose it over and over again, that we prioritize it, that we never drift too far away from it, and that it always sits just beneath the surface of our thoughts and actions even when the mat or cushion isn’t literally under our feet. But when enthusiastic dedication shifts into inattentive and involuntary performance, then yoga and habit have uncoupled. That is the time to challenge your habits.

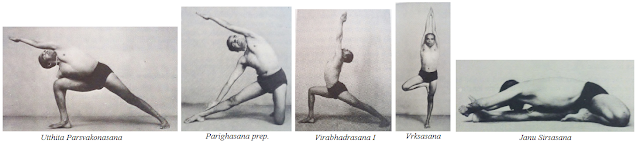

Below is the sequence of postures we are exploring on Sunday mornings for a few weeks. I didn’t create this sequence; it is part of the course we are (pseudo) following in the back of Light on Yoga. I have, however, modified it to reflect those poses which are appropriate for our group of students. If you are interested in exploring the sequence in its entirety (or in modifying it in some other way), then feel free to look it up (pagse 464-65).

It is fairly typical to save inverted postures (here I namely mean Sirsasana and Sarvangasana variations) for the end of a practice. Commonly, standing poses (including Sun Salutation variations), some back bends, hip openers, and maybe arm balances precede these poses. There is good reason for that, which I am not going to elaborate on here, but have in the past and surely will again in the future.

Note, however, that this particular sequence opens with inversions. It starts with a long series of Sarvangasana poses. In fact, part of what I left out, but which you can see and try for yourself if you follow along in the book, is that the sequence actually starts with a series of Sirsasana poses. If you are not accustomed to beginning your practice upside down, and/or your inverted postures are most familiar to you only following a long “warm-up” or preparation period, then this will be very different to you. It will be weird, it will feel awkward and tight, and it will be eye-opening. It has been my experience as both a student and a teacher of this sequence that it will reveal things to you about your body, your breath, and your mind that you have never been aware of before.

It is not just about opening with inversions. This sequence puts several poses in unconventional places and orders, and does not necessarily “prepare” you for them in the way that you may be used to. For example, there is a series of strong core-focused poses very early before much has been done to wake up the trunk, which calls upon an even healthier does of effort on your part than these poses tend toward ordinarily. Then, in a way that feels odd and abrupt, you stand for Fierce pose and then kneel for Camel pose. The legs, which have been almost entirely in the air up to this point, feel wobbly. And the shoulders and upper-back feel toned and sturdy after the inversions, which isn’t a bad thing by any means, except that these back bended shapes need a kind of openness and mobility which you may not have.

It is challenging, but the novelty and rawness is exhilarating. And it just may be the perfect antidote for a practice drowning in habit. Move mindfully, act conservatively, and pay attention. Everyone’s practice is unique, and this particular series of events may not be the kind of habit-challenging experience you need. That’s fine. Find something that is. Confront yourself. Challenge your habits.

*Modified* version of the 19th to 21st Weeks sequence of Course I as presented by B.K.S. Iyengar in Light on Yoga

Salamba Sarvangasana I – Supported Shoulderstand first variation

Salamba Sarvangasana II – Supported Shoulderstand second variation

Halasana – Plow pose

Karnapidasana – Ear-pressing pose

Supta Konasana – Supine Angle pose

Parsva Halasana – Side Plow pose

Ekapada Sarvangasana – One-legged Shoulderstand

Parsvaikapada Sarvangasana – One-legged Side Shoulderstand

Urdhva Prasarita Padasana – Supine Leg Lifts pose

Jathara Parivartanasana – Supine Twist pose

Paripurna Navasana – Full Boat pose

Ardha Navasana – Half Boat pose

Utkatasana – Fierce pose

Ustrasana – Camel pose

Virasana – Hero pose

Salabhasana – Locust pose

Dhanurasana – Bow pose

Chaturanga Dandasana

Bhujangasana – Cobra pose

Urdhva Mukha Svanasana – Upward-facing Dog pose

Adho Mukha Svanasana – Downward-facing Dog pose

Janu Sirsasana – Head-toward-knee Forward fold

Triangmukhaikapada Paschimottanasana – One-leg Hero Forward fold

Paschimottanasana - Seated Forward fold

Marichyasana I – Marichi’s Forward fold first variation

Bharadvajasana I – Bharadvaja’s twist first variation

Baddha Konasana – Bound Angle pose

Savasana

Siddhasana with Ujjayi