I was recently working with a group of students on the components of belly-down back bends which is really tough stuff. They are deceptively challenging poses because from the outside they appear to be petty plain, even easy, but a whole lot is happening just beneath the surface. Poses like Salabhasana (Locust, 100), Makarasana (Crocodile, 101), and Dhanurasana (Bow, 102) require strength in your legs and all along your spine - front and back - as well as openness in your hips, chest, and shoulders. Part of their challenge comes from the effort it takes to lift yourself up against gravity. Not only is that difficult by itself, but it is made even more so in this case because you can't use your arms for help. And, even though in the long-run they actually serve to improve respiration, lying prone sometimes makes breathing feel restricted. So, while they are "simple" and "fundamental" poses, they are not by any means easy. And for that reason we were discussing the purpose and importance of these poses in an effort to encourage continued practice of them.

During the class I made a kind of off-handed remark about Locust pose being one of the most important postures; possibly in the top five of all time if you were to make yourself a list. Later on I found myself thinking about that comment, and I wondered what would my top-five asana list actually include?

Mr. Iyengar provided his own list of "important asana" in LoY, and I have already commented a little on that (see previous post: "Most Important Asana"). I think his is a great compilation of fundamental postures that nearly anybody would benefit from (see disclaimers below). Although mine does overlap with his, that wasn't conscious on my part; it just speaks to the merit of the poses. And given a list longer than five, mine would differ slightly (see below).

A few things should be kept in mind as I share this with you. First, this is solely my opinion. This is what seems appropriate to me given my experiences as a student and an instructor. Other people, with other experiences or other trainings, may have different opinions. And none of us would be right or wrong, just different.Secondly, the list does not take into consideration contraindications. By that I mean the list assumes that you are capable of performing each of the poses in their full (or nearly full) form free from any overt risk of injury. I do not mean to imply that you mustn't need the assistance of props or some kind of modification, but that the basic form of the pose is accessible and appropriate for you. If, for instance, you recently suffered a neck injury, you shouldn't be performing Shoulderstand as that is explicitly contraindicated. However, if your neck, spine, and shoulders are generally healthy and fit, but stacked blankets help you maintain good alignment, then you can practice Shoulderstand. In other words, if any of the poses are inappropriate for your practice, then your list would need to be adjusted accordingly.

Thirdly, by "most important" I do not mean favorite poses or the most fun poses or the ones most frequently requested. This is not a list based on popularity. I promise you that if the list were titled "my personal favorite poses to practice because I love them and they feel good," it would be a very different list. What I mean is these are the poses whose basic forms and functions provide the most benefit to a general practice; the ones which are arguably the most advantageous physically and metaphysically. Their teachings are deep and multi-layered, and continue to be so whether we have practiced them one time or a thousand times.

Lastly, Tadasana (Mountain pose, 61) and Savasana (Corpse pose, 463) are implicitly listed as they are essential elements of postural practice. Do not think that I am ignoring them, and do not discredit them for yourself. They are imperative.

With that being said, here, in no particular order, is my list of the five most important yogasana:

- Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-facing dog, 110)

- Salabhasana (Locust, 100)

- Salamba Sarvangasana I (Supported Shoulderstand first variation, 205-13)

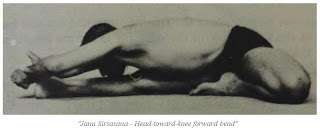

- Janu Sirsasana (Head-toward-knee forward bend, 149)

- Prasarita Padottanasana (Wide-angle forward bend, 81)

I'll make a few comments to explain each of my choices.

Adho Mukha Svanasana. Even though I said the list was presented in no particular order, if there were an order, I would put AMS in first place. This singular pose contains a nearly complete practice all by itself. It provides stability and strength to the legs which are toned into a neutral "Tadasana" position. It also generously stretches the legs from the buttocks through the heels. It opens the hips and pelvic-floor. It tones the abdomen. It lengthens the spine. Its weight-bearing component adds upper-body strengthening which prepares you for arm-balancing and inverting. It stretches the arms, shoulders, and side-body. It opens and loosens the upper-back. It is an inversion because the hips are higher than the heart and the heart is higher than the head. But because the feet stay anchored, it is less strenuous than more overt inversions such as Headstand and Shoulderstand which makes it a more appropriate choice for some people. In that way it serves as either a preparation or a replacement for upside-down poses. It can serve as a warm-up before activity or a cool-down afterward because, by adjusting just a few key actions, it can energize or soothe. It is known to have positive effects on the nervous system as a whole, including respiration, brain function, blood circulation, and heart health. And it is the beginnings of understanding the idea of "root down in order to rise up" which is vital for both physical and metaphysical growth. It is really unparalleled.

Salabhasana. The primary function of Locust pose is to strengthen the spine's extensor muscles. And it performs that job so well that the pose is a common exercise in many modalities beyond yoga such as Pilates, gymnastics, body building, physical therapy, and more. The reason why it is so effective is because the muscles all along the back are getting undivided attention. By that I mean there is no assistance coming from other body parts, namely the arms as is the case in many other back bends. When you include the arms in a pose like Cobra, for instance, the action is split between a back bend and a push-up. That is not bad, of course; Cobra and poses like Cobra are fantastic. Unfortunately, it is common to allow the strength of the arms to override the capacity of the spine, and then the bend is deeper or the lift is higher than is optimal. In Locust the extensors get to do precisely what extensors do best without any interference or peer-pressure coming from other muscle-groups. In that way it teaches patience, humility, and self-reliance. Additionally, the effort it takes to lift the body up against the force of gravity enhances its effectivenes. And, because the front body is compressed against the floor, the organs of digestion, elimination, and reproduction receive needed stimulation.

Salamba Sarvangasana I. The basic form of Shoulderstand is such a tremendously powerful pose. Of course there are risks involved (every yoga pose involves risk), and it is not appropriate for everybody. However, if you are capable of practicing it, even in a prop-supported or slightly modified way, do so. I will let what Mr. Iyengar has written about its benefits suffice for explanation as it is clear and thorough, and I could not add anything to it to make it any better. If you have not read the Shoulderstand (205-13) and Shoulderstand Cycle (213-37) sections in LoY, I highly recommend it.

Janu Sirsasana. In Sanskrit janu means "knee" and sirsa means "head," so the name of this pose suggests that the head comes to the knee when the truth is that, if the spine is properly elongated, the chin comes to rest on the shin rather than on the knee. If that form of the pose is achieved, along with the recommended width of the thighs, adequate external rotation of the back leg, sufficient reach of the arms, and proper positioning of the trunk, then the pose provides ample opening for the hips; stretch for the legs, back, and side bodies; and elasticity for the upper-back and shoulders. It conditions the internal organs, including stimulating the kidneys, and its deep forward fold is calming.

Most of the seated forward bends share those positive effects. What differentiates Janu Sirsasana, and grants it a position on the list of five, is that it serves as the foundation, the model, for the rest of the seated work: Janu Sirsasana is the seated cousin of Tadasana. From this pose emerge the variations of forward folds in which one leg is in lotus (153-55), hero (156-59), and squat (159-61); those in which the torso is revolved (152, 162, 165, 172) and/or the arms are bound (154, 160-163); the wide-legged variations (164); and the symmetrical forward folded posture known as Paschimottanasana (166-70).

It seems counterintuitive to think that the straight-legged, symmetrical fold would develop after the more pretzel-y asymmetrical folds, but the truth is that it takes the full conditioning of the legs, hips, spine, belly, and arms received by the one-legged poses to properly prepare the body for Paschimottanasana. There are comments in LoY further explaining this idea on pages 148-70, particularly pages 157, 161, and 170.I think that the series of seated forward folds is the most difficult category of asana, more so than back bends, arm balances, and even inversions. That is primarily because of their relationship to gravity (which limits our ability to manipulate the pelvis and activate the core) in combination with our culturally-developed biomechanical habits (i.e. our tendency to slouch works against us in these poses). As a whole, the collection of poses is meant to provide cleansing and stimulating effects on the internal organs as well as calming effects on the nervous system. But before we can experience those things, Janu Sirsasana needs to be well understood.

Prasarita Padottanasana. LoY provides two variations of Wide-legged forward fold: the one pictured here in which the hands are placed on the floor between the feet, and the one in which the hands are joined behind the back. Other styles of practice recognize other versions of this pose, both formally and informally, and I recommend them as an effective series with this first variation serving as the starting point.

Like all the standing poses, this pose strengthens and tones the feet and legs. It also stretches the legs from the buttocks to the heels very much like AMS. Different from AMS though, and perhaps advantageous to come, is that there is less weight-bearing in the upper-body. Therefore it may be more appropriate for those with wrist or shoulder injuries. Also like AMS, it is an inversion without the stress of lifting the feet. And it serves as either a preparation or a replacement for going upside-down. Because the legs are widened, it is typically more accessible and therefore performed more skillfully, than the narrow-legged version known as Uttanasana (93). If the hands are placed according to the instructions, there is some conditioning for the wrists, arms, shoulders, and even the upper-back. And those effects are enhanced when attention is paid to the "back bended stage" of the pose in which the back is given ample extension.

Even though standing poses such as Triangle, Side-angle, and the Warriors are incredibly important poses, my opinion is that the added benefits of mild weight-bearing and inverting provide enough advantage to this pose to place it on the list of five (within the bounds of the disclaimers mentioned earlier). It also has the perks of wrist, shoulder, and chest stretching when other variations are considered.Five poses is not very many; it makes for tough decisions. What is missing here, for better or worse, are postures whose primary purpose is twisting, balancing (both arm and leg), and core-strengthening. If the list were expanded to ten or even fifteen, I would likely include poses from those categories. It would be something like this:

Top Ten

- Trikonasana (Triangle pose)

- Virabhdrasana I (Warrior pose first variation)

- Supta Padangusthasana (Reclined Hand-to-big-toe pose, plus variations)

- Virasana (Hero pose)

- Jathara Parivartanasana (Reclined twist, plus variations)

and Top Fifteen

- Navasana (Boat pose)

- Vrksasana (Tree pose)

- Ustrasana (Camel pose)

- Bakasana (Crow pose)

- Baddha Konasana (Bound Angle pose)

I admittedly put less thought into the secondary lists, so I cannot say I am fully committed to their content. But you get the idea.

The list of five can serve as a foundation for a more full-spectrum postural practice; it can be an outline from which to proceed and grow. It can also be a condensed practice all by itself when time or energy is limited. It could be a way of warming up when you arrive a few minutes early to class. And maybe, for any number of good reasons, you disagree with my list either partially or entirely, in which case you could make a different list for yourself.

Whatever asanas are practiced, however few or many, in whichever forms or levels of skill, the poses serve an important purpose: they better the body as a means of bettering the "something-more-than-your-body." They are an embodiment of the gross serving as a gateway to the subtle; of the material providing access to the spiritual. They affect us in ways that we see and feel, and in ways which are wholly imperceptible. I'll end with a few words regarding asana by Mr. Iyengar:

The yogi conquers the body by the practice of asanas and makes it a fit vehicle for the spirit. ... By performing asanas, the [yogi] first gains health, which is not mere existence. It is not a commodity which can be purchased with money. It is an asset to be gained by sheer hard work. It is a state of complete equilibrium of body, mind, and spirit. ... The yogi realizes that his life and all its activities are part of the divine action in nature, manifesting and operating in the form of man" (41).

(All quotes, images, illustration numbers, and page numbers refer to: Iyengar, B.K.S., Light on Yoga. New York: Schocken Books, 1979. Print.)