“I was doing too many backbends…; one day I made up my mind to do forward bends like Janu Sirsasana—I could not stay in it even for a few minutes. My spine and back muscles became sore and I couldn’t bear the soreness… It was as if somebody was using a sledgehammer on my back. Then I determined that if I could do backbends, I should learn to do forward bends too.”

B.K.S. Iyengar, Yoga Wisdom & Practice, 16

Whereas back bending postures create broad and expansive arches, forward bends are more about precise edges and crisp creases. That’s not to say that forward bends are severe or unpleasant. The opposite, in fact, is true. When performed well, forward bends are soothing and rejuvenating; they also provide their own kind of expansive softness. They just require a different kind of action, and they create a different kind of shape for the body to experience. Back bends bring to mind Roman architecture and orbiting planets. Forward bends are more reminiscent of origami.

The key to successful forward bending, or to making origami art, is knowing how to apply the right balance of commitment plus suppleness in order to fold in the right places with the right amount of pressure. Also like origami, forward bending poses require beginning with simple and basic folds. And the more intricate the fold is, the higher the risk that something could go wrong.

Seated forward bends always have their foundation in Dandasana (Staff, 112). Its 90-degree bend at the hips makes it the first and most basic fold. From there it would seem like the least complex and most straightforward next step would be to fold the body over the legs into what is known as Paschimottanasana (Seated Forward-fold, literally “intense stretch for the back-body pose”, 166). This asana has been called the king of all forward bends, and its potential positive effects are abundant, including improved cardiovascular health, rest for the nervous system, and stimulation for the circulatory system. But it’s a mistake to confuse its apparent simplicity for easiness to perform. While it primarily consists of just one crisp fold at the hips, it is actually a more intricate shape to achieve than it appears. In fact, Light on Yoga states that this pose is only truly accessible after mastering the complex and asymmetrical seated folds.

Four poses are said to be the “preparatory poses for the correct Paschimottanasana.” They are Janu Sirsasana (Head-toward-knee, 148), Ardha Baddha Padma Paschimottanasana (Half Bound Lotus Forward fold, 155), Triangmukhaikapada Paschimottanasana (Three Parts Facing West Forward fold, 156), and Marichyasana I (Marichi’s Twist first variation, 160). While these four poses certainly have more components involved, more folds to manage, they also “give one sufficient elasticity in the back and legs so that one gradually achieves the correct Paschimottanasana” (161).

We worked on Janu Sirsasana in class together last week, so let’s start there. It is an intricate shape wherein the necessity for precision is great, but if we carefully unfold the posture, we can see that it is just a series of much more basic shapes and folds bundled together.

There are three important basic shapes to recognize in the legs and hips. First, the foundation is, of course, Dandasana, and the front leg maintains that shape throughout—straight, strong, and anchored. The back leg is a little more complex as it is a combination of two different basic shapes. So the second important thing to recognize is that the back leg is externally rotated at the hip as well as bent deeply at the knee in a shape which mimics Baddha Konasana (Bound Angle, 128) or, maybe more accurately, Siddhasana (Adept’s Seat, 120). Finally, the distance between the two legs is important and often gets overlooked. The instructions are to “push the [back] knee as far back as possible” so that the “angle between the two legs [is] obtuse” (149). That means the position of the thighs is like that of Upavistha Konasana (Wide-angle Forward fold, 164). Take a look at those poses next to each other, and see if you recognize the repetition of shape.

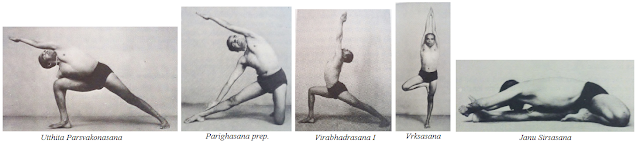

The upper-body includes familiar shapes as well. The asymmetrical work of poses such as Parsvakonasana (Side Angle, 67) and Parighasana (Gate, 86) prepare the trunk, shoulders, and hips for Janu Sirsasana by concentrating on just one side of the body at a time. But the full form of Janu Sirsasana aims to eliminate any asymmetry above the hips, which means it definitely has threads of relationship to poses such as Virabhadrasana I (Warrior I, 71) and Vrksasana (Tree, 63).

Mr. Iyengar and Light on Yoga are not the only sources of high praise for Janu Sirsasana and its closely related postural cousin, Triangmukhaikapada Paschimottanasana. That’s a lot of Sanskrit, I know. It sounds something like tree-AHNG-mook-eye-kuh-PA-duh POSH-chee-moh-tan-AHS-uh-nuh. And the English translation is not any better—“three parts facing west seated forward fold.” It’s a tongue-twister, for sure, and, unfortunately, practicing the pose can feel as awkward and foreign as trying to pronounce its name. If you were in class with me this week, you got a sense of that for yourself as this was our focus for practice.

They are challenging, yes, but I promise that these poses are worth learning—posturally and linguistically. Both of them are part of the Ashtanga Primary Series as well as Light on Yoga’s “Course One.” One of my favorite texts which expounds on the Ashtanga system of practice is called Ashtanga Yoga: Practice & Philosophy by Gregor Maehle. Even if you don’t practice Ashtanga Yoga, it is a fantastic manual. And it is my go-to resource second only to LoY.

In it, Maehle says that, other than the jump-backs and jump-throughs which are a pivotal part of the Ashtanga practice, Triangmukhaikapada Paschimottanasana is one of the “main producers of abdominal strength” in the Primary Series. That is because it is abdominal strength which keeps the sitting-bone of the bent leg anchored against the ground. He says that a student first learning this pose “often makes the mistake of focusing too much on the forward-bending aspect of the posture. It is much more important to ground the [buttock of the bent leg], which works directly on the hip and develops abdominal strength” (77). He calls it a “humble posture” which is “one of the most underestimated” (78).

Light on Yoga also comments on the abdominal strengthening aspect of this pose. It says that “this asana tones the abdominal organs and keeps them free from sluggishness,” and then goes on to say that we often “abuse our abdominal organs by over-indulgence and by conforming to social etiquette” which causes disease. We can gain “longevity, happiness and peace of mind” by practicing these two essential postures (157).

About Janu Sirsasana, Maehle says that it, “like no other posture, combines the two main themes of the Primary Series—forward bending and hip rotation.” That also happens to be a primary theme of LoY’s Course One. Maehle describes Janu Sirsasana as being identical to performing Paschimottanasana with one leg and Baddha Konasana with the other, and that “there may be more exhilarating postures in the sequence, but it is [this pose] that most lets us experience the underlying principles of the [Primary Series]” (79).

Maehle also emphasizes the benefit of patiently practicing the “back bended stages” of these two poses as well as other seated forward folds. He says that, while it might make you look or feel stiff, it is more elegant, and, more importantly, knowing how to maintain “the inner integrity of the postures makes the practice far more effective” (78).

Creating the proper elongation, precise edges, and crisp folds which these poses require is not easy. It takes time, patience, and humility, among other things. It is an art form, and your body is your medium. Like an origami artist with her paper, there must be both precision and yielding. With attention to the details, you fold and bend and twist to create something beautiful and affirming from the inside out.

We will continue to explore these poses, and similar ones, in the weeks ahead.

Iyengar, B.K.S. Yoga Wisdom & Practice: For health, happiness, and a better world. London: DK Publishing, 2009. Print.

Maehle, Gregor. Ashtanga Yoga Practice & Philosophy. Novato: New World Library, 2006. Print.